In this Virginia History Blog, we look at recent journal reviews concerning the New South and Civil Rights eras. “The Dooley’s of Richmond” charts the business, commercial and philanthropic achievements of two generations from 1836 to 1922.

“The Uplift Generation” examines the interracial efforts of whites and blacks to achieve greater equality for blacks in a “separate but equal” regime of Jim Crow from 1900 to 1930. “Richmond’s Priest and Prophets” chronicles the efforts of white religious leaders in the 1940s and 1950s to end segregation in public arenas.

Current releases related to Virginia history in other eras from Spring 2018 journals can be found in previous Virginia History Blogs at Colonial Virginia – Spring 2018, Revolutionary Virginia – Spring 2018, and Civil War Virginia – Spring 2018.

The Dooleys of Richmond

Mary Lynn Bayliss wrote The Dooleys of Richmond: An Irish Immigrant Family in the Old and New South in 2017. Reviewed in the Journal of Southern History. Available from the University of Virginia Press, Kindle and online new and used.

This book chronicles the lives of affluent and well educated Richmonders John Dooley (1811-1868) who immigration in 1836, and his son James Henry Dooley (1841-1922). The Dooley family business was begun in the hat making business that became one of the largest manufacturing companies in the United States. Both expanded investments in railroads over two generations.

John Dooley was an early investor in railroads, acquired slaves and became influential in states rights politics. He voted for John C. Breckenridge, and he and his sons served in the Confederate Army. At the same time, John supported Irish independence and hosted activists such as John Mitchel in fund raising activities. After the Civil War, James Dooley launched into industrial and land development, making him one of the richest men in Richmond, becoming a substantial philanthropists and a key figure in the industrialization of the New South. He actively defended white supremacy and joined the Conservative Party to overthrow Reconstruction.

To buy “The Dooleys of Richmond” on Amazon, click here.

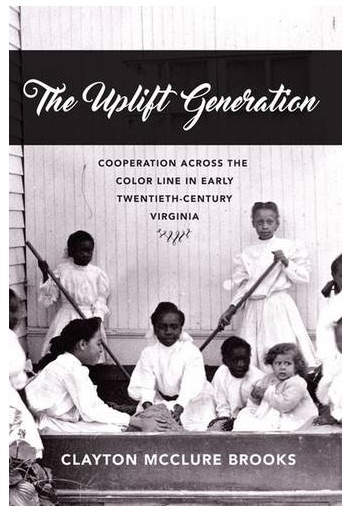

The Uplift Generation

Clayton McClure Brooks wrote The Uplift Generation: Cooperation Across the Color Line in Early Twentieth-Century Virginia in 2017. Reviewed in the Journal of Southern History. Available from the University of Virginia Press, Kindle and online new and used.

This book analyzes the interracial activism promoting the advancement of the black race in the South from 1900 to 1930, and their gradual awareness that the movement was a failed tactic. A paternal white elite saw segregation as humanitarian, a Progressive reform consistent with contemporary gentility. It was also a Jim Crow regime of Lost Cause imaginings recalling a benevolent slave regime past. They took pride in Virginia’s lowest rate of lynching among states where racial lynching occurred. The “better classes” of uplift black Virginians, who were mostly Richmonders embracing Booker T. Washington’s philosophy, saw accommodation with segregation as a means to harness racism to make “separate but equal” as equal as possible, focusing on child welfare, public health and education.

Many black leaders such as W.E.B. Dubois believed that active military service in World War I would be a powerful argument against segregation. Richmond leaders included John Mitchel, Jr., editor of the Richmond Planet. But racial restrictions in Virginia and elsewhere only intensified after the war. Interracial cooperation diminished. The accommodationist strategy was rejected in the African American community as accomplishing little, and an increased emphasis on voting rights evolved.

To buy “The Uplift Generation” on Amazon, click here.

Richmond’s Priest and Prophets

Douglas E. Thompson wrote Richmond’s Priests and Prophets: Race, Religion, and Social Change in the Civil Rights Era in 2017. Reviewed in the Journal of Southern History. Available from the University of Alabama Press, Kindle and online new and used.

This book examines how white Christian leaders in Richmond, Virginia, both preserved their religious communities as “priests” and sought to overturn segregation as “prophets” in the 1940s and 1950s. Desegregation in the old capital of the Confederacy occurred less dramatically than other southern capitals such as Little Rock, Arkansas, in part due to the groundwork laid by these religious ministers who changed how their congregations thought about race, both intellectually and emotionally.

The umbrella organization of the 1950s was the Richmond Ministers’ Association (RMA) which included both Protestants and Catholics. Their efforts included shaming segregationists in letters to the editor of Richmond’s editorials and in articles appearing in white Christian newspapers. In the face of massive resistance to the schools integration ordered by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education, many public calls for change failed to achieve immediate practical results. But churches of the 1950s held a place of power generally in American society and in Richmond in particular. The process was nuanced, minds came to be changed slowly. Religion played an important role in American political life.

To buy “Richmond’s Priests and Prophets” on Amazon, click here.

Additional history related to Virginia during this time period can be found at the Table of Contents of TheVirginiaHistorian website on the page for Gilded Age, New South and 20th Century. Titles are organized by topics, political and economic Virginia, social history, gender, religious, African American, and Wars in Virginia 1750-1824.

General surveys of Virginia History can be found at Virginia History Surveys. Other Virginia history divided by topics and time periods can be found at the webpage Books and Reviews.

Note: Insights for these reviews include those available from articles in the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, the William and Mary Quarterly, the Journal of the Civil War Era, the Journal of Southern History and the Journal of American History.