We begin the second of four blogs focusing on African American History in Antebellum Virginia with a look at the rise of the domestic slave trade after the legal prohibition of the trans-Atlantic trade in the Middle Passage from Africa with “A Troublesome Commerce” and “Carry Me Back”.

At the same time half a million slaves were transported south out of Virginia, it developed the largest free black population. They are discussed in “Slaves without Masters” and “Free Blacks in Norfolk, Virginia”, along with pioneers of free black education in the Antebellum South in “Three Who Dared”.

The last two of our blog related to the idea of manumission and free colonization as a middle ground between universal abolition and perpetual slavery. This is addressed in “Slavery and the Peculiar Solution” and “Virginia’s Ninth President: Joseph Jenkins Roberts”.

These books are all used in bibliographies found in peer-reviewed surveys of Virginia history of scholarly merit. Additional insights are used from articles in the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, the Journal of Southern History and the Journal of American History.

For book reviews at The Virginia Historian.com in this historical period for other topics, see the webpage for Antebellum, Civil War, Reconstruction. General surveys of Virginia History can be found at Virginia History Surveys. Other Virginia history divided by topics and time periods can be found at the webpage Books and Reviews.

A Troublesome Commerce

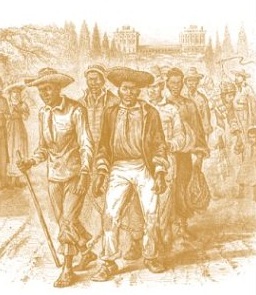

A Troublesome Commerce: The Transformation of the Inter-state Slave Trade in 2003; it is in limited supply. This intellectual history studies the domestic slave trade primarily from Virginia southwest between 1820 and 1850. It begins with an overview of the many kinds of forced migration for slaves. These included movement with relocating planters before the 1830s, increasingly the sale away by owners remaining behind during the cotton boom and throughout, the kidnapping of free blacks.

Gudmestad describes the rise of the domestic slave trade and the change in white southern conceptualization of the practice, from early objections to the practice as a threat to the morals of society by breaking up slave families, to a unified justification defending the removal of surplus workers in the border states and fuelling cotton expansion in the Deep South.

The publication of Walker’s Appeal and Nat Turners Rebellion operated as a push and the pull was from the vertical integration of supply, transport and resale under the dominant trading firm Franklin, Armfield and Ballard based in Alexandria, Virginia. Learn more to buy “A Troublesome Commerce” here for your bookshelf.

Carry Me Back

Steven Dyle wrote Carry Me Back: The Domestic Slave Trade in American Life and it was reprinted in paperback in 2006; it is readily available. Dyle offers a comprehensive study of the domestic slave trade. It guided the nation to a civil war on both sides. Even after ending legitimate slave trade from Africa, Abolitionists objected to it domestically in the nation’s capital and in interstate trade. Slaveholders saw an economic threat to their capitalization in slave property for the cotton boom and chose secession rather than chance slavery’s eventual demise.

While border state owners distanced themselves from the human trade by blaming disgruntled slaves and despised slave traders, the lower South essentially blackmailed Virginia into the Confederacy by threatening to cut off their continued forced migration of surplus slave labor. Learn more to buy “Carry Me Back” here for your bookshelf.

Slaves Without Masters

Ira Berlin wrote Slaves Without Masters: The Free Negro in the Antebellum South in 1974. It is out of print but can be found used online. Because he was a human being the Negro as slave was a troublesome property, and as a free citizen he was a troublesome anomaly. The free black eventually secured strategic positions in the Southern economy that made deportation by colonization and at the same time the free black community in the Upper South created economic competition with poor whites.

Free blacks in the Upper South were more numerous, mainly rural and seen as a potential cause of slave unrest. Those in the Lower South were lighter in color, largely urban and economically better off than slaves. In both regions they were not revolutionary, but sought independence and respectability in the face of rampant racism. They established their own churches, schools, fraternities and benevolent societies. Learn more to buy “Slaves Without Masters” here for your bookshelf.

Free Blacks in Norfolk

Tommy Bogger wrote Free Blacks in Norfolk, Virginia, 1790-1860: The Darker Side of Freedom in 1997. It is out of print but can be found used online. For free blacks, antebellum Virginia was seventy years of rising institutionalized racism along with declining educational and employment opportunities. In Norfolk, almost half of those gaining freedom during these years did so by self-purchase, not by a master’s manumission. After the rebel Gabriel was captured in Norfolk, legislators restricted the already modest legally protections afforded blacks.

Freedom was threatened by a loss of a freedom certificate, or kidnapping into permanent Lower South slavery. Free blacks labored in a city where slaves were rented out, and they were faced with an increasing European immigrant community taking away artisan and draymen jobs. It was a precarious existence under an increasingly hostile racial environment. Unlike Philadelphia, the free black community in Norfolk provided more individuals willing to be colonized in Africa, to begin anew in a foreign land. Learn more to buy “Free Blacks in Norfolk” here for your bookshelf.

Three Who Dared

Philip S. Foner and Josephine F. Pacheco edited Three Who Dared: Prudence Crandall, Margaret Douglass, Myrtilla Miner — Champions of Antebellum Black Education in 1984. It is out of print but can be found used online. Three white women brought controversy and legal censorship on themselves in Canterbury, Connecticut, Washington, D.C., and Norfolk, Virginia. Quaker Prudence Crandall received help from Friends charitable contributions, and ran a girls school for free blacks in Canterbury from 1833-34, marrying a controversial Baptist minister. Myrtilla Minor was horrified by slavery teaching at a girl’s school in Mississippi, and founded a school for free black girls supported by Quakers and Abolitionists from 1851 to 1864.

Margaret Douglass was not an abolitionist. Raised in Charleston, the single mother and member of the Christ Church Episcopal Church where matrons taught slave children to read. Douglass agreed to supplement earnings from tailoring vests with tutoring free black children to read. She was jailed for a month without a defense from the lawyer members of her church. Learn more to buy “Three Who Dared” here for your bookshelf.

Slavery and the Peculiar Solution

Eric Burin wrote Slavery and the Peculiar Solution: A History of the American Colonization Society in 2005 and it was reprinted paperback in 2008. It is a series of essays on issues raised by the American Colonization Society (ACS) which sought to repatriate those of African descent back to Africa, both free blacks and manumitted slaves. African Americans migrating often had kinship relations, membership held themselves out to be anti-slavery, leadership stressed the ACS was not abolitionist, and southern whites routinely denounced the ACS as disrupting the social stability of slave society.

Early settler free slaves from Maryland and Virginia were joined by manumitted slaves primarily from the Upper South. Deep South whites who emancipated slaves were primarily born in the Upper South. Virginians and Kentuckians were prominent in ACS leadership, and most emancipated slaves originated from plantations owned by prominent slave owning families such as the Pages, Cockes and Randolphs. About 6,000 were emancipated by 560 slave owners among the approximately 15,000 African Americans migrating to Liberia before the Civil War. Learn more to buy “Slavery and the Peculiar Solution” here for your bookshelf.

Virginia’s Ninth President

C. W. Tazewell edited Virginia’s Ninth President: Joseph Jenkins Roberts in 1992. It is out of print. Joseph Jenkins Roberts was son of a free black Petersburg family who became the Governor and then first President of Liberia. Though used as a source in Wallentsein’s survey history of Virginia, “Cradle of America”, it was written by an amateur historian and was not reviewed in the history journals readily available online.

For book reviews at The Virginia Historian.com in this historical period for other topics, see the webpage for Antebellum, Civil War, Reconstruction. General surveys of Virginia History can be found at Virginia History Surveys. Other Virginia history divided by topics and time periods can be found at the webpage Books and Reviews.