In this Virginia History Blog, we look at the New South and Modern Virginia part one, with titles relating to Civil Rights and Social History.

Civil Rights in the New South and Modern Virginia. Two titles from Summer 2018 include “A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time” on Alexandria in the Civil War and Gilded Age DC, and “The Dream is Lost”, investigating voting rights and the subsequent politics of race in Richmond. A historical perspective for racial integration is presented in three additional titles, “Right to Ride” on streetcars, “With All Deliberate Speed” on public schools, and “Freedom’s Main Line” on the Freedom Rides and reconciliation.

Social History in the New South and Modern Virginia. “Contemporary Community Identity” describes the controversy in , “Three Generations, No Imbeciles” shows the political and legal role of eugenics in Virginia, expanded by “Segregation’s Science”. “The Body in the Reservoir” investigates the role of the sensational press in a Richmond trial.

Civil Rights Virginia

A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time

Paula Tarnapol Whitacre wrote A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time: Julia Wilbur’s Struggle for Purpose in 2017. It is available from the University of Virginia Press, on Kindle and online new and used. Reviewed in the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Buy the “A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time” on Amazon here. A companion to Elizabeth Keckley Behind the Scenes: Or, Thirty Years a Salve and Four Years in the White House (1868, 2017).

Julia Wilbur was a single woman who embraced two radical movements during her lifetime: abolition and women’s suffrage. For several years she worked to improve the conditions of freed slaves. A New Yorker born to Quaker parents, Wilbur was early on influenced by witnessing lectures by Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Frederick Douglass. Though not a prominent leader, she became a committed civic activist. Whitacre discloses a character who is self-pitying and brave, foresighted and petty.

Leaving her career as a free public school teacher in Rochester, Wilbur relocated to Alexandria, Virginia at 47 in 1862. She was employed as a “relief agent” sponsored by the Rochester [NY] Ladies Anti-Slavery Society to serve the ballooning population of “contraband” escaped slaves entering Union lines and relocating to Alexandria for work. After the war she became a “visiting agent” for the Freedman’s Bureau until 1869 when she secured a position as a clerk in the Patent Office where she worked until her death twenty five years later. Wilbur increasingly committed herself to the women’s suffrage movement.

Buy the “A Civil Life in an Uncivil Time” on Amazon here. See also Mary Lynn Bayliss The Dooleys of Richmond: An Irish Immigrant Family in the Old and New South (2017), Brian Burns Gilded Age Richmond: Gaiety, Greed and Lost Cause Mania (2017).

The Dream is Lost

Julian Maxwell Hayter wrote The Dream is Lost: Voting Rights and the Politics of Race in Richmond, Virginia in 2017. It is available from the University Press of Kentucky, on Kindle and online new and used. Reviewed in the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography and the Journal of American History. Buy the “The Dream is Lost” on Amazon here.

Hayter narrates many of Richmond’s contributions to the struggle for African American political freedom over three decades. While the Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965, unintended consequences and political abuses followed. The black community’s lack of political power contributed to the structural displacement of families into 1980s housing projects that continue to be plagued by violence.

Beginning in 1956, the Richmond Crusade for Voters was an important advocate for political change, and by the 1960s, its registration drives threatened white control of the city. But annexation of twenty-three square miles of Chesterfield County in 1969 forestalled a majority black city council until 1977.

In 1982, Dr. Roy West, an African American educator, secured the support of white city council members to be elected Mayor over the opposition of the Richmond Crusade. That lead Crusade consultant Sa’ad El-Amin to exclaim, “The dream is lost”. By Hayter’s analysis, a new political dynamic had produced division in the black community due to the growth of the city’s black middle class that was not solely governed by race identity.

Buy the “The Dream is Lost” on Amazon here. See also J. Douglas Smith Managing White Supremacy: Race, Politics, and Citizenship in Jim Crow (2003), and Benjamin Campbell Richmond’s Unhealed History (2012).

Right to Ride

Blair L. M. Kelley wrote Right to Ride: Streetcar Boycotts and African American Citizenship in the Era of Plessy v. Ferguson in 2010. It is available from the University of North Carolina Press, on Kindle and online new and used. Buy “Right to Ride” on Amazon here. A companion to Tera W. Hunter To Joy my Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors after the Civil War (1998), August Meier and Elliott Rudwick From Plantation to Ghetto (1970), Kenneth W. Goings and Raymond A. Mohl The New African American Urban History (1996), and Pamela E. Brooks Boycotts, Buses, and Passes: Black Women’s Resistance in the U.S. South and South Africa (2008).

Kelley investigates streetcar boycotts in Jim Crow Richmond, Savannah, and New Orleans – the precursors to the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott. These were once viewed by historians as “accomodationist” due to association with Booker T. Washington and “class biases”. All was not passive silence and non-confrontation in these challenges to second-class citizenship. There were divisions in the black middle class in tactics and strategies. Working class African Americans played a significant role and black women contributed in ways usually ignored.

Boycott leaders marshaled church organizations and newspapers, networked steering committees and held mass meetings. They sponsored alternative forms of transportation, collected political petitions and underwrote legal action reaching across class and color lines.

Buy “Right to Ride” on Amazon here. Also coauthored by this scholar, From the Grassroots to the Supreme Court: Brown v. Board of Education and American Democracy (2004). See also Winifred Breines The Trouble Between Us: An Uneasy History of White and Black Women in the Feminist Movement (2006).

With All Deliberate Speed

Brian J. Daugherity and Charles C. Bolton edited With All Deliberate Speed: Implementing Brown v. Board of Education in 2008. It is available from the University of Arkansas Press, on Kindle and online new and used. Buy “With All Deliberate Speed” on Amazon here.

In this book of twelve essays, Daugherity and Bolton explore the actual process of achievements and failures that unfolded to implement the Supreme Court’s ruling to integrate public schools. Virginia is included in the survey of seven southern states, three border states and three northern states. African Americans challenged Jim Crow segregation in the schools to secure equal educational opportunities. Many hoped that an alliance between blacks and moderate whites enabled by the courts might bring integrated schools. But the courts were ineffectual and southern moderates were marginalized.

Segregationist delay tactics were far more effective in sustaining de facto racially separated schools and they were sustained over a longer period of time than violent or histrionic massive resistance. In the end, the delays were in effect long enough for white flight to take effect across county lines into surrounding suburbs. Despite efforts at cross-district bussing, the issue of integrated classrooms for most populations became largely moot. The growth of private academies in rural areas and the Supreme Court allowing racial divides in an urban region in Milliken v. Bradley (1974) led to a South “less segregated than in 1954 but more segregated than 1980”.

Buy “With All Deliberate Speed” on Amazon here. Also by this author, Keep On Keeping On: The NAACP and the Implementation of Brown v. Board of Education in Virginia (2016).

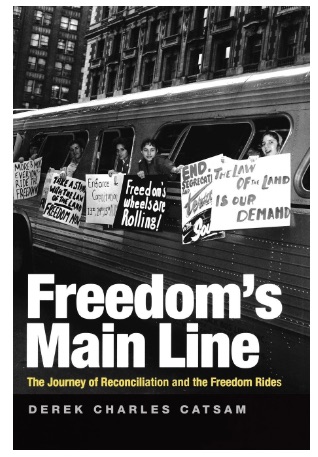

Freedom’s Main Line

Derek Charles Catsam wrote Freedom’s Main Line: The Journey of Reconciliation and the Freedom Rides in 2008. Available from the University of Kentucky Press, Kindle and online new and used. Buy “Freedom’s Main Line” on Amazon here.

This book is one of a series in the University of Kentucky’s series on “Civil Rights and the Struggle for Equality in the Twentieth Century”. It integrates the 1961 Freedom Rides sponsored by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) into the context of other civil rights activities, contemporary politics and the pervasive Cold War milieu. Attention is paid to the complex relationships among civil rights organizations.

Catsam is careful to document Irene Morgan in Virginia and several other examples of resistance confronting racial discrimination and segregation. See Morgan v. Virginia (1946), and Boynton v. Virginia (1960). Local and national transportation systems served a central role in spotlighting discriminatory race relations in Virginia. While federal inaction was often cloaked in appeals to federalism, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s nonviolence campaigns were sometimes supplemented by local reliance on armed self-defense in response to beatings. The American Nazi Party commissioned the “Hate Bus”, White Citizens’ Councils sponsored the “Reverse Freedom Ride”. The Interstate Commerce Commission called for integration in interstate transportation in 1961, but realization often awaited developments in local and state politics. When their elected officials called for obeying the law, most whites accepted integration in public places, however reluctantly.

Buy “Freedom’s Main Line” on Amazon here. See also Thomas A. Bruscino A Nation Forged in War: How World War II Taught Americans to Get Along (2014), August Meier Negro Thought in America, 1880-1915 (1963), and Wilson J. Moses Classical Black Nationalism: From the American Revolution to Marcus Garvey (1996).

Social History in Virginia

Contemporary Southern Identity

Rebecca Bridges Watts wrote Contemporary Southern Identity: Community through Controversy in 2008. Available from the University Press of Mississppi, Kindle and online new and used. Buy “Contemporary Southern Identity” on Amazon here.

This book of communication scholarship studies public rhetoric from opposing sides in four controversies related to southern identity from 1989 to 2002. The Virginia subjects are about admission of women to the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), and integrating public art displays in Richmond to include African Americans among Confederate figures. The two others are flying the Confederate battle flag over the South Carolina Statehouse, and U.S. Senator Trent Lott’s (R-MS) praise of the career of U.S. Senator Strom Thurman (R-SC).

Watts shows the disagreement about how to characterize the likeness of southern identity and its diversity. Characteristic of all sides is a concern over the “order of division” following from historical perspectives about slavery, secession, states’ rights and segregation. Participant statements are recounted along with an historical context for each point of view, and Watts sees agreement among them that the debate over being “southern” is culturally important. The region is transforming racially as seen in these four episodes because in each one an exclusion that had been long enshrined and taken-for-granted was overthrown. Yet at the same time southerners are mutually concerned with preserving what they perceive to be a distinctly regional identity.

Buy “Contemporary Southern Identity” on Amazon here. See also John Shelton Reed The Enduring South: Subcultural Persistence in Mass Society (1986), David Potter Southern Sectionalism and 20th Century Nationalism (2012), W. J. Cash The Mind of the South (1991), and Richard Weaver The Southern Tradition at Bay: A History of Postbellum Thought (1989).

Three Generations, No Imbeciles

Paul A. Lombardo wrote Three Generations, No Imbeciles: Eugenics, the Supreme Court, and Buck v. Bell in 2008. Available from the Johns Hopkins University Press, Kindle and online new and used. Buy “Three Generations, No Imbeciles” on Amazon here.

In 1927, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of a Virginia statute authorizing the institutionalization of institutionalized “mental defectives” who were judged most likely to “produce socially inadequate offspring”. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote for a unanimous Supreme Court, that in the Buck family case, “three generations of imbeciles are enough”. The grandmother, mother Carrie Buck and daughter were ruled to be a burden on society and dangers to themselves. Beginning with Indiana in 1907, Progressive reformers had begun adopting sterilization laws. After the Buck case, more than a dozen more states adopted sterilization laws in the 1930s, eventually growing to a high of thirty-three.

The superintendent of the state Eugenics Records Office coordinated with the head of the Virginia Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-minded to bring a test case of his Model Sterilization Law. Despite elaborate procedures in place, including the right to a lawyer and to call witnesses in a hearing, inmates were often were not informed that they were to be or that they had been sterilized. Lombardo presents evidence that Buck and her daughter were not imbeciles. But the defense lawyer who was on the board on the Virginia Colony arguably failed Carrie Buck “because he intended to fail” so as to justify his belief in sterilization of the socially inadequate.

Buy “Three Generations, No Imbeciles” on Amazon here. See also Adam Cohen Imbeciles: The Supreme Court, American Eugenics, and the Sterilization of Carrie Buck (2016), Michael Rembis Defining Deviance: Sex, Science, and Delinquent Girls, 1890-1960 (2013), and Jonathan Peter Spiro and William Wynn Westcott Defending the Master Race: Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant (2015).

Segregation’s Science

Gregory Michael Dorr wrote Segregation’s Science: Eugenics and Society in Virginia in 2008. Available from the University of Virginia Press, Kindle and online new and used. Buy “Segregation’s Science” on Amazon here.

In this intellectual and legal history of race and the study of racial improvement in Virginia, Door explores the Progressive impulse developing in the early twentieth century. Eugenics largely shaped racial theory in the early twentieth century. It became a justification for racial purity and segregation of blacks from whites, sick from the healthy, able from the disabled, and fit from the unfit. These were codified in 1924 by the General Assembly in the Racial Integrity Act and in the notorious sterilization law passed the same year. Virginia physicians performed one-eighth of all American eugenic sterilizations from 1927 to 1980.

Eugenics developed into racist mainline thinking as promulgated by turn of the century University of Virginia professors interpreting Thomas Jefferson’s racial views and applying them to public health, government, and the “survival of the [racially segregated] social order” to benefit the most “fit” residents of Virginia. These principles were subsequently enacted into law and enforced in public health departments, state hospitals and courts. It then morphed into concerns of neo-Malthusian overpopulation and increasing costs of welfare programs. Old Stock Virginians were legislatively insulated from the one-drop rule by a exception for descendants of Pocahontas and John Rolfe.

Buy “Segregation’s Science” on Amazon here. See also Jason Morgan Ward Defending White Democracy: The Making of a Segregationist Movement and the Remaking of Racial Politics, 1936-1965 (2014) and Paul A. Lombardo A Century of Eugenics in America: From the Indiana Experiment to the Human Genome Era (2011).

The Body in the Reservoir

Michael Ayers Trotti wrote The Body in the Reservoir: Murder and Sensationalism in the South in 2008. Available from the University of North Carolina Press, Kindle and online new and used. Buy “The Body in the Reservoir” on Amazon here. See also Richard F. Hamm Murder, Honor and Law: Four Virginia Homicides from Reconstruction to the Great Depression https://amzn.to/2OC397u (2003).

Using sources from both white and black newspapers published in Richmond, Virginia, Trotti makes significant forays among several historical eras to look into the role and changing character of sensationalism in the capital city. It examines southern distinctiveness, modernity, and race by following developments in crime reporting as it became more regular and lengthier, more lurid and unrelenting following the Civil War.

The book is focused on the alleged murder of Lillian Madison by Thomas Cluverius in 1885. Trotti draws comparisons between press and public reaction to the death of this young, unmarried and pregnant woman with a number of other murders, including a earlier case in 1867 of Mary Phillips murder by her husband, the murder of Lucy Pollard, a white farmer’s wife by four accused African Americans charged in 1895, and the shotgun murder of Louise Beattie by her husband in 1911.

Changing cultural, legal, and journalistic conventions shaped reporting and interpreting facts in a murder case and influenced changes in popular perception of each tragedy. Central in the transformation in crime reporting was the change from pamphlet sketches to photography. In Richmond, the sensational 19th century penny press did not establish an outlet until the eve of the Civil War, but by the 20th century, the Richmond press would cover “disreputable women and even some sexual content”. At first, John Mitchell’s black newspaper the Richmond Planet promoted sensationalism in crime accounts to crusade for the acquittal of accused African Americans. But it later shifted to an emphasis on reporting on the “good, upstanding” African Americans to further social connections with the “respectable classes” of whites.

Buy “The Body in the Reservoir” on Amazon here. See also Daniel Cohen Pillars of Salt, Monuments of Grace: New England Crime Literature and the Origins of American Popular Culture, 1674-1860 (1993, 2006), Karen Halttenuen Confidence Men and Painted Women: A study of middle-class culture in America, 1830-1870 (1982), and her Murder Most Foul: The Killer and the American Gothic Imagination (1998, 2000).

TVH Era Webpage for Gilded Age, New South, 20th Century

The TVH webpage for Gilded Age, New South, 20th Century Eras, 1880-Present, features our top title picks taken from the bibliographies of three surveys of Virginia History’s 400 years.

The Table of Contents divides Political and Economic Virginia, 11880-Present into (a) Gilded Age to mid-20th century policy, and (b) Mid-20th century to present policy. Topical history is treated under headings of Social History, Gender in Virginia, and Religious Virginia.

African American Virginia, 1880-present is divided into (a) Jim Crow Virginia 1880-1950, and (b) Civil Rights Virginia, 1950-present. Finally, wars are featured under (1) Spanish American War, (2) World War I, (3) World War II, and (4) Cold War.

See Also

General surveys of Virginia History can be found at Virginia History Surveys. Other Virginia history divided by topics and time periods can be found at the webpage Books and Reviews.

Note: Insights for these reviews include those available from articles in the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, the William and Mary Quarterly, the Journal of the Civil War Era, the Journal of Southern History and the Journal of American History.